Drop dead again? New film finds NYC’s 1975 fiscal crisis still haunting the city today.

April 20, 2025, 10 a.m.

“Drop Dead City,” a new documentary about New York City teetering on the brink of bankruptcy and ruin in 1975, premieres at the IFC Center on Friday.

The mayor of New York City is widely seen as incompetent. Inflation is near record highs as the wider economy slows, subway ridership is down while the MTA faces a growing budget gap, and the White House is threatening to pull the city’s federal funding over political disagreements.

This archaic scenario is the subject of “Drop Dead City,” a new documentary premiering at the IFC Center on Friday that is about New York City's 1975 fiscal crisis, which sent it teetering on the brink of bankruptcy and ruin.

The movie premiered to a sold out audience at the DOC NYC festival in October and won the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns film prize. It takes its name from the infamous New York Daily News headline “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.” In October 1975, President Gerald Ford vowed to veto any bill that offered federal funding to help NYC avoid bankruptcy.

Despite its focus on events 50 years ago, the film raises striking parallels with the present, as New Yorkers face political dysfunction and divestment, a contentious immigration boom, and fundamental disagreements with the federal government over what a society owes to its people.

While the topic of a financial crisis is relatively dry, the 103-minute film is a visual delight for anyone who enjoys footage of vintage New York City.

There are classic Cadillacs and Volkswagen Beetles backed up on the Brooklyn Bridge while striking city workers block their path; mounds of trash in the streets during a sanitation strike; lanes of the West Side Highway collapsing while buildings burn; and more 1970s outfits, accents, sideburns and side characters than “Saturday Night Fever,” all set to a funk and soul soundtrack that would make Quentin Tarantino’s music supervisor bow in respect.

It also depicts a New York City that may be unfamiliar to those who’ve lived in the years since the “Disneyficiation” of Times Square.

Filmmakers Michael Rohatyn and Peter Yost worked with archival producer Frauke Levin to source miles of 16mm camera footage from the era, digging into city archives as well as the back catalogs of PIX11, Getty and the major news networks.

Yost is a longtime documentary director and producer. First time co-director Rohatyn, a composer, is also personally connected to the material: His father Felix Rohatyn chaired the Municipal Assistance Corporation, which was given the power to issue new debt under state auspices. Under Felix, CUNY began to charge tuition, subway fares rose, wages were frozen, and there were widespread layoffs of public workers. Felix, who died in 2019, appears in archival footage.

“I think he had to make very tough choices and that was something that he hated to do,” Michael Rohatyn said. “For dad, it’s a paradox – he revered FDR and the New Deal. I don’t know what would have happened if someone with a different point of view had been given the role.”

The archival footage was incredibly expensive to license, Rohatyn said, which is one reason the project, which began in 2017, was not released until now. Winning $200,000 in the Library of Congress prize wasn’t sufficient to cover the costs, but helped get them over the line.

“This is basically why people don’t make movies like this,” Rohatyn said. “It’s just too expensive, and only an idiot and a novice would undertake it.”

The broad strokes of the story are familiar to older New Yorkers or devoted fans of its history, but may be a revelation to younger audiences.

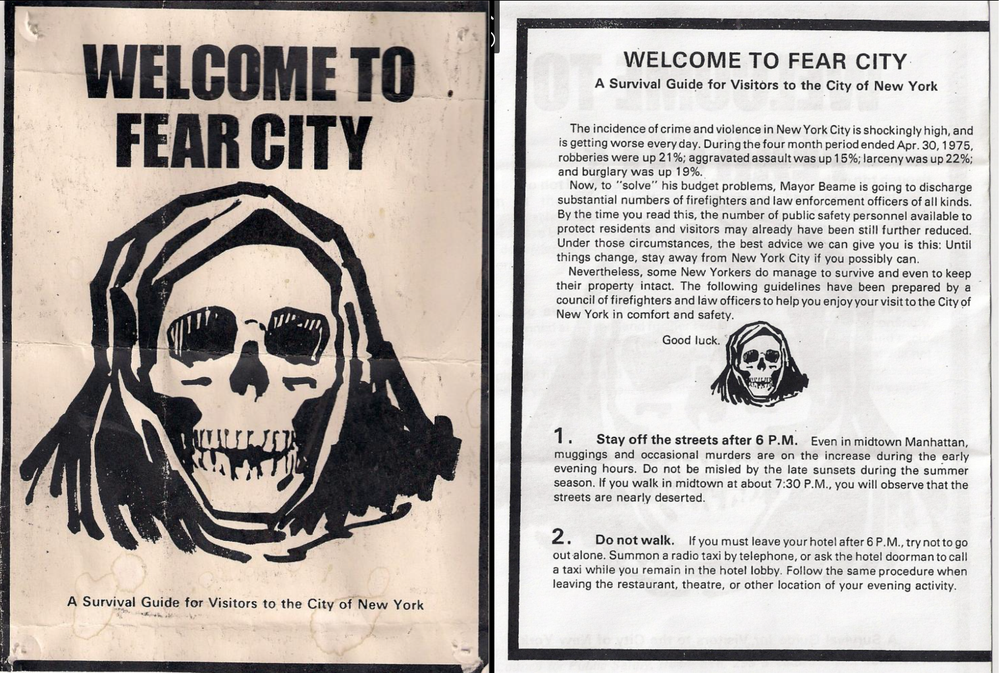

After World War II, New York City represented New Deal liberalism in its fullest expression, according to Kim Philips-Fein, a Columbia historian and author of “Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics,” a 2018 Pulitzer Prize finalist.

“There was a very strong sense of the purpose of city government, and the ethos of the city was to create a decent place for working-class people to live,” Philips-Fein said.

CUNY was tuition-free, rent regulation and public sector employment were widespread, and there was a deep investment in the arts and a booming network of public hospitals and primary care clinics, she said.

“If you go into city schools even today, you can sometimes see an office labeled ‘Dentist’s Office,’” Philips-Fein said. “That was where kids in New York got dental care, was in the public school system.”

This was challenged on all fronts by the crises of the 1970s, according to historian Kevin Baker, who consulted on “Drop Dead City” and appears in it.

A combination of economic stagnation and inflation eroded the wages of well-paid union workers and led to recession in the early 1970s, just as an immigration boom in New York led to “white flight” and disinvestment while simultaneously increasing the demand for social services, Baker said.

The receding good times revealed that the city’s finances were a mess, with a monstrous and widening budget deficit. The city and state’s ongoing emergency measures failed to fix the problem, and Mayor Abe Beame drafted a statement declaring the city’s bankruptcy, which he signed but never put into effect thanks to a last-minute deal with the teacher’s union to raise revenue. Finally, the city turned to the White House for help, leading to Ford’s famous refusal.

Philips-Fein sees a clear parallel to the Trump administration’s willingness to interrupt the flow of federal funds to the city.

“Playing games with these millions of dollars that actually affect real people’s lives is a real echo of the ‘70s,” Philips-Fein said. “Again today there’s a sense that New York, as a center of immigration with a long history of protest, is going to come in for special punishment.”

Philips-Fein also sees parallels in the austerity politics that followed the 1970s crisis and today.

“The cuts, when they came, hurt poor people and Black and Latino people the most in the city, but there was something random about the cuts as well,” Philips-Fein said. “It wasn’t as though they followed an extremely clear fiscal or even social logic. The federal government had a sense of being willing to let havoc reign, a kind of cavalier glee at causing chaos that has echoes to what we see today.”

Philips-Fein sees the austerity of the 1970s as leading to the “nihilistic spirit of late ‘70s early ‘80s New York,” when the government seemed to turn from solving social problems to simply managing decline amid rising crime, drug use, and a sense that the city was ungovernable.

“These bonds, these institutions, this public spirit and sense of democracy as a real lived experience, this is something to treasure that’s built up over many years,” Philips-Fein said.

“Reductions in public services and public institutions have their own multiplier effect that can drive people to turn against or leave the city,” she said. “They’re important not just because they give people a set of services but because they create the conditions that allow democracy to function. Losing them is a profound loss that can take generations to build back or recover.”

10 great restaurants to visit in the West Village, no matter your budget Inside the auditions for the New York Liberty’s over-40 dance squad Even NYC influencers are sick of New York mega-influencers