Cleopatra's Needle, the Central Park obelisk, holds secrets we'll never know

Feb. 24, 2022, 5:01 a.m.

It's the oldest outdoor monument in New York, and it holds time capsules that the Central Park Conservancy has no plans of unearthing.

The obelisk in Central Park, also known as Cleopatra's Needle, was formally dedicated on February 22nd, 1881 after a long trip involving ships, cannonballs, and the sharp corners put in place by the Commissioners' Plan of 1811. At over 3,500 years old, it's the oldest man-made object in Central Park, the oldest outdoor monument in New York, and it has a story that includes ancient Egypt's Temple of the Sun, Cecil B. DeMille, the complete works of Shakespeare, and a journey for the ages.

It also holds not one, but two time capsules, and this week the Central Park Conservancy (CPC) confirmed with Gothamist that we'll never see what's inside of them.

But let's start at the beginning.

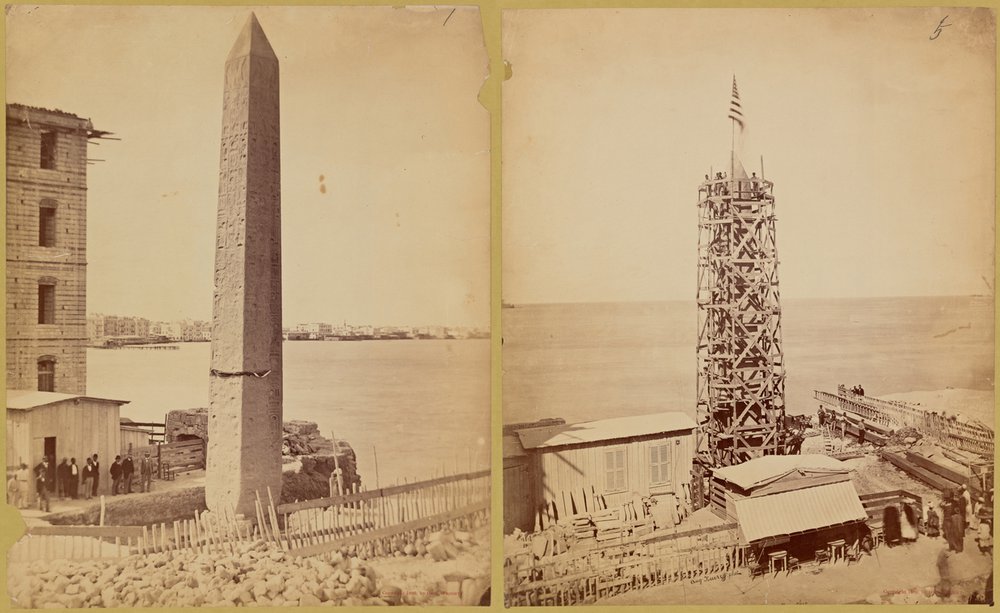

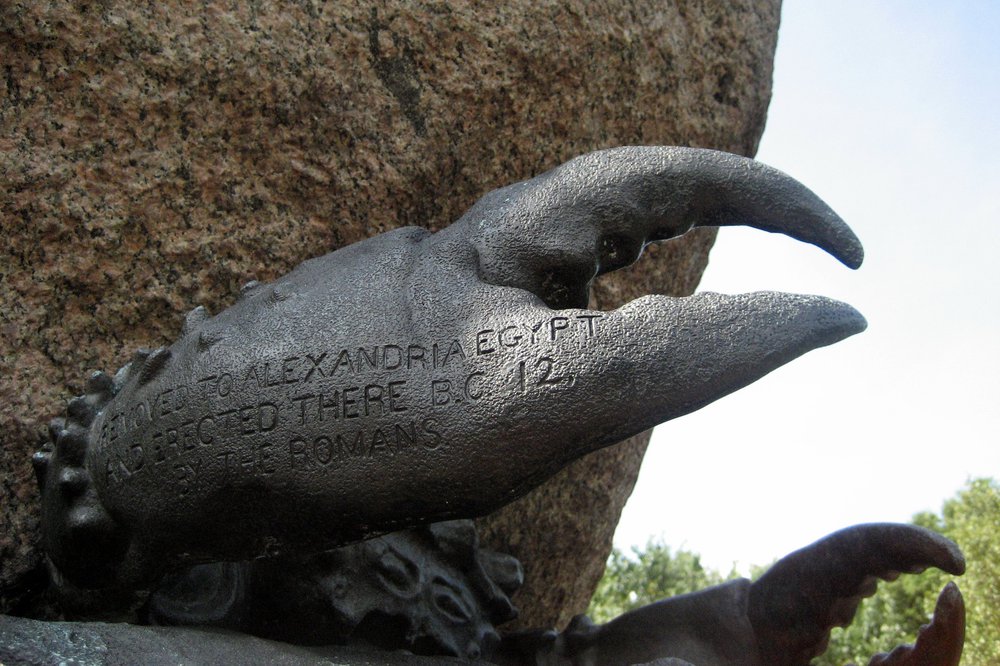

Originally created in the ancient Egyptian city of Heliopolis, the obelisk was one of two created for a celebration for Pharaoh Thutmose III. Both of the nearly 70-foot-tall structures were installed outside of the Temple of the Sun, and with each weighing in around 200 tons, they stayed there for quite some time — 1,500 years, to be exact. At that point, they were toppled during an invasion, and according to the Central Park Conservancy (CPC), "For more than 500 years, they remained buried in sand until Roman Emperor Caesar Augustus discovered and transported them to Alexandria."

Once there, they were placed outside of the Caesareum, a temple created by Cleopatra in honor of Julius Caesar.

Time passed, the Caesareum became a Christian church, and eventually, the Egyptian government decided to give away the two obelisks. One went to London and one to New York City. And so the journey began in Alexandria.

This was an era of gifting between countries — around the same time, France was discussing sending over the Statue of Liberty.

"Both took years to finalize, and the obelisk beat the Statue of Liberty by three years," Sara Cedar Miller, Central Park Conservancy Historian Emerita, told Gothamist. "So they are two major monuments that we associate with gifts from other countries."

According to the CPC, the site of the obelisk — Greywacke Knoll, between the then-newly opened Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Great Lawn — was chosen over Columbus Circle, Grand Army Plaza, and Union Square, because placing it in Central Park "ensured that it wouldn't be overshadowed by skyscrapers" (not that the city was overrun with true skyscrapers at the time). It likely also had something to do with William H. Vanderbilt, who funded its travels, pushing for that location.

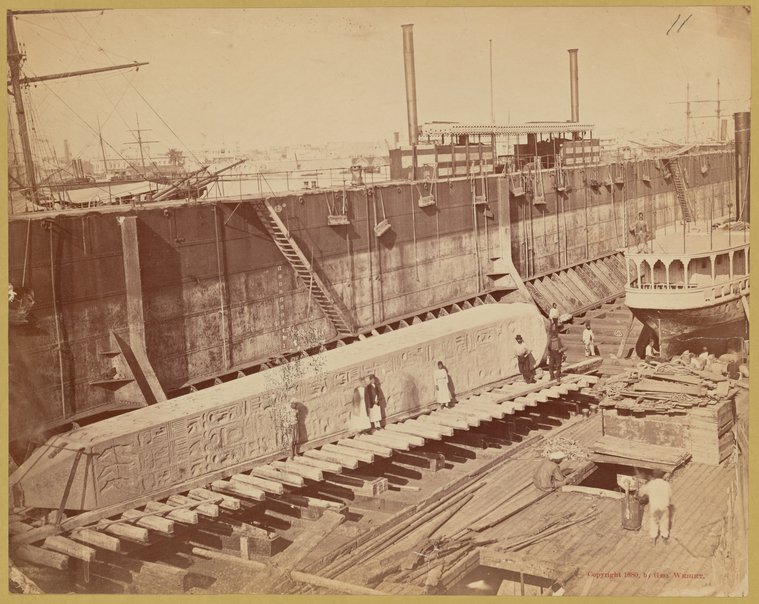

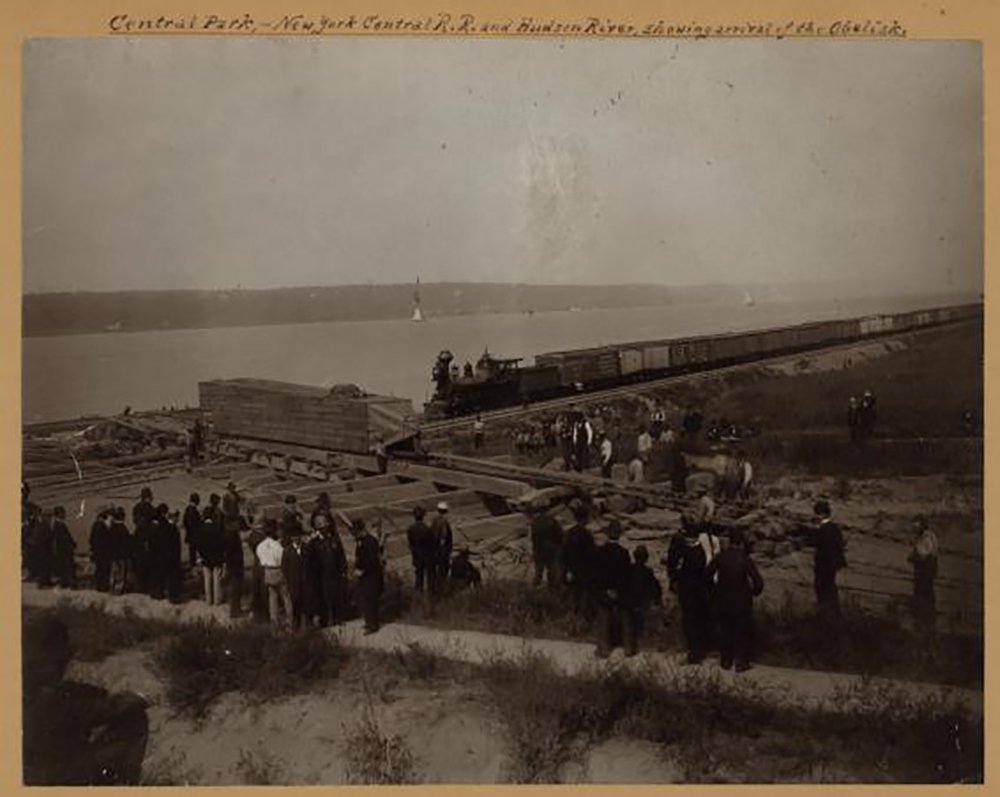

While the Statue of Liberty was delivered in around 350 pieces, with its arm first displayed in Madison Square Park in 1876, the obelisk had to be sent whole, along with its 50-ton pedestal. When it finally reached the shores of New York, it was brought to Staten Island first, transferred to a new vessel, and then brought across the river to the Upper West Side. From there, it had to cross a specially-built bridge and was then transported via a rail track built for the occasion, moving around just one block a day towards its final destination.

"It had to go from the Hudson River on these specially built rails, rolling with cannonballs through all of New York City, this very large object around the corners of our [street] grid," Miller said.

The journey through the city took 19 days, and once it reached Fifth Avenue, it sat for 20 more, the final leg of the trip delayed by a blizzard. Once it was sitting still, the CPC noted that some New Yorkers arrived "with chisels hoping to get a piece of the stone," and a 24/7 security team was put in place to protect it.

The obelisk finally went from horizontal to vertical on January 22nd, 1881 — an event that drew around 10,000 people — but it wasn't dedicated until one month later when a formal ceremony was held at the Met.

Not everyone had been a fan — the New York Times printed a few criticisms of the decision to bring the obelisk here. In 1879, they wrote, "There is no longer any hope that we shall escape the Alexandria obelisk," questioning what it was a monument to, as well as "the passion for removing Egyptian obelisks and erecting them in foreign countries." They asked, "What right do we have to remove the landmarks of archeology, and show ethnological tares for posterity to reap?"

But New Yorkers went wild for the obelisk — Miller dubbed it, "Obeliskmania," and said locals "flocked to see every little stage of it," from its arrival to its installation.

In Martina D'Alton's book on the structure, she wrote, "Obelisk fever gripped the city. One entrepreneur set up a candy stand that traveled alongside the obelisk [and] fashionable restaurants offered a new drink, the Obbylish, which was served with a needle-shaped swizzle stick." One outlet called the beverage "an unparalleled morning awaker," but sadly, the recipe appears nowhere.

If you visit the obelisk today, you'll see each corner is supported by bronze crabs — these are 900-lb replicas cast from the originals. The originals, crafted by the Romans, are on display at the Met.

You'll also find plaques that translate the hieroglyphics — these were paid for by Cleopatra director, and native New Yorker Cecil B. DeMille.

Miller, of the CPC, said DeMille "fondly remembered playing there as a boy." He was born in 1881, just months after the obelisk arrived, and in his epic The Ten Commandments, he even included an obelisk-raising scene.

While it's a common sight by now, the structure still holds some mystery and intrigue. Before it was erected, time capsules were placed under it. One includes the 1870 census, a Bible, a dictionary, the complete works of Shakespeare, a guide to Egypt, and a facsimile of the Declaration of Independence. But the other ... no one knows.

"The most fascinating thing is a small black box capsule that was put into the ground by the man [William Henry Hurlburt] who orchestrated the purchase and the transportation of the obelisk. He died being the only person who knows the contents of that box," Miller said. (Note: Hurlbut helped spearhead the campaign to bring the obelisk here, though it was a gift, some aspects — like travel — needed funding, just like with the Statue of Liberty.)

The Central Park Conservancy confirmed this week that there are no plans to ever unearth the capsules, given the complex logistics that would be involved, given the weight of the structure.

Mary Caraccioli, CPC's chief communications officer, told Gothamist, "It would likely be too difficult to move the obelisk in order to get the time capsules."