Beloved NYC design store seeks new home for its extensive archive

Nov. 3, 2023, 11:30 a.m.

KIOSK has until Thanksgiving to move its museum-ready archive out of storage.

New Yorkers of a certain vintage will remember the store KIOSK, which lived downtown from 2005 to 2015. If you’d been there, how could you not?

“It was kind of the dream ‘New York secret spot,’” said Chay Costello, the associate director of merchandising at the MoMA Design Store. “That maybe you know about, that other people don’t know about.”

The shop, or design museum, or rotating folk art installation, was always a little hard to describe. For one, you had to find it.

The store has been online only since 2015, but its first home was at 95 Spring Street, a building since torn down to make room for Nike’s gargantuan store on the corner of Spring and Broadway.

If you managed to find the doorway and navigate one floor up the graffiti-covered, pre-war stairwell, you found yourself transported far from the increasingly unrecognizable, hypercommercial neighborhood that was swirling frantically into being outside.

It was a place where you could find simple items from around the world, curated and arranged so that customers understood who made the objects and why they mattered.

Now, the beloved emporium is looking for a new home for its archive of more than 1,500 objects – with a deadline of Thanksgiving to vacate from its current space.

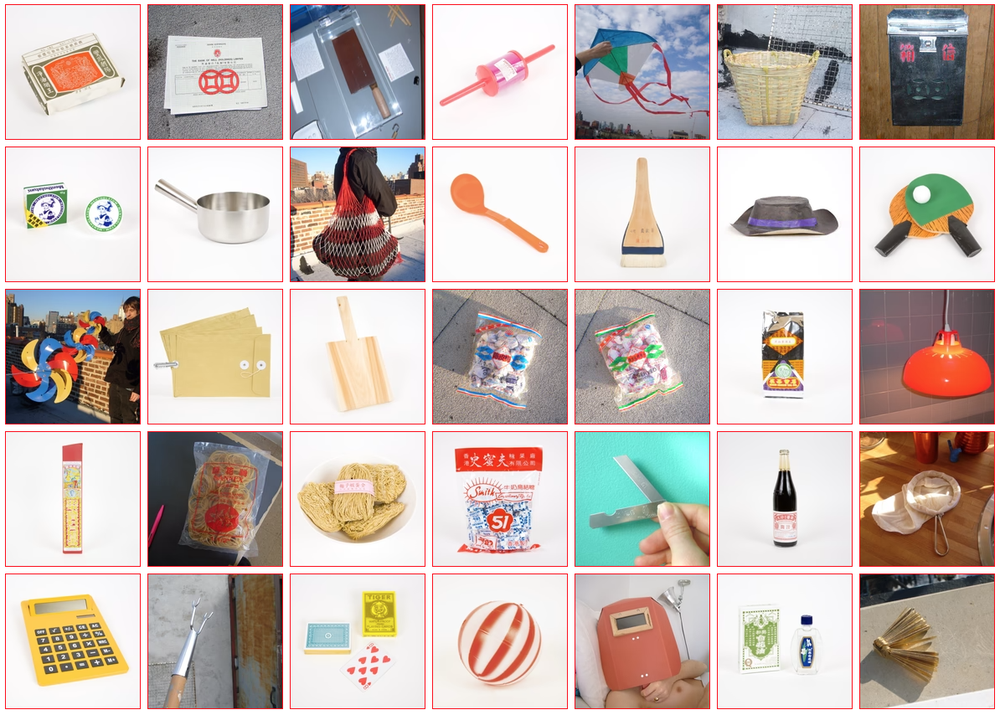

KIOSK was a retail experience unlike any other. Here’s how it worked: partners Alisa Grifo and Marco ter Haar Romeny would visit an interesting place – in Japan, say – and hang out for a while, meeting people, getting to know them, embedding.

In the course of their travel, they would identify everyday objects that hadn’t been widely seen outside their local context before – scotch tape dispensers and slippers, a surprisingly flashy bag or a long-handled spoon, rubber bands, nice paper, a red-tipped crowbar– and bring them back to the shop.

“There’s so much anonymous design that doesn’t have a designer’s name imprinted on it,” ter Haar Romeny said. “We were trying to find things that were beautiful or functional, or maybe evoked some emotion in us.”

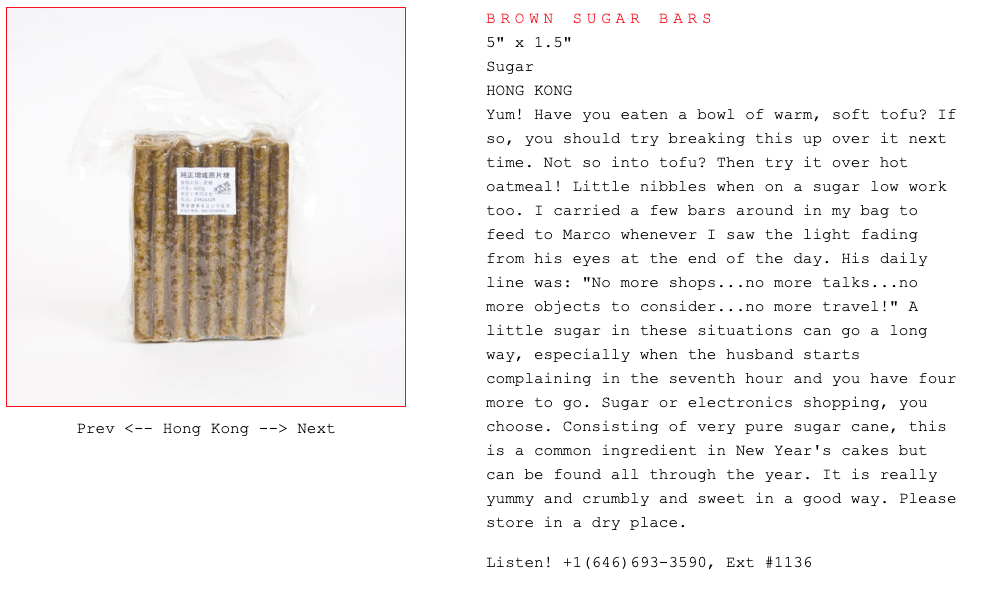

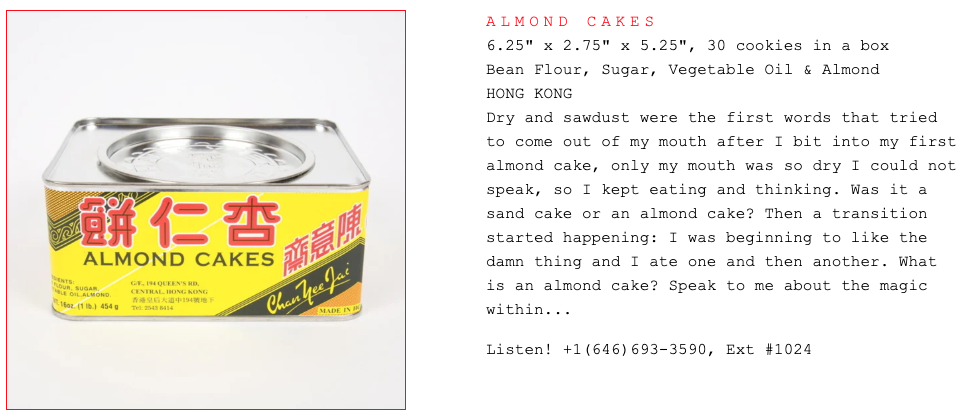

Back at the shop, each trip’s haul was organized into a collection and displayed like a museum exhibit, with object descriptions in Grifo’s singular style.

For a time, each label carried a phone number with a unique extension that you could dial to hear a description.

“We would talk about the history of the object or the experience of visiting the factory,” Grifo said. “Or just why we found something attractive, or if we had a personal relationship to it.”

“We wanted a store that we liked to go to,” ter Haar Romeny said.

“Everything would have this very poetic, sweet description of who made the product, why they were including it, and what it meant to that culture at large,” recalled Dusen Dusen designer Ellen Van Dusen.

In the years since KIOSK first opened, Van Dusen explained, plenty of retailers have discovered the importance of telling their products’ stories. Back then, she’d never seen anything like it.

“It was a totally unique experience,” Van Dusen said. “They treated it all as art, and yet it was priced to take home – even for someone who was 22, like me.”

One block east, Costello and her colleagues at the MoMA Design Store had noticed.

“When we saw what KIOSK was doing, we recognized a simpatico spirit,” Costello said. She eventually worked with Grifo to bring some objects from KIOSK’s Germany collection into the MoMA store.

“Alisa was almost like a prototype of a lifestyle influencer, before that was a term we used,” Costello said.

The products, though basic, were imbued with value by the story behind them.

“All of a sudden maybe you’re fantasizing that you’re living in France, or you’re spending the summer in Greece,” Costello said. “You get transported through the experience of what KIOSK was doing.”

After nine years on Spring St., KIOSK moved to two short-lived locations on Union Square and LaGuardia Place, before wrapping up their brick and mortar operations in 2015. That year, MoMA PS1 showed their collection as part of its “Greater New York” exhibit.

Since then, they’ve had itinerant displays in London and Marseille, and a gallery exhibit at Gordon Robichaux in 2019, but no permanent retail display.

From the start, the couple realized that several of their favorite objects were fast disappearing from the global marketplace.

“Even six months later, I would go back to reorder something and it would be gone,” Grifo said. “So pretty early on, we realized we should keep one of each thing.”

The KIOSK Archive, now comprising more than 1,500 objects, was born.

Grifo, who describes herself as an “organizational nut,” says the archive is carefully packed with conservation materials and filed into the same bins that museums use for storing art, each item neatly labeled and numbered with accompanying spreadsheets.

Ter Haar Romeny says the whole archive fits in about 3/4ths of a one-car garage.

“We just over time couldn’t afford it,” Grifo said. “With Covid, storage spaces became increasingly expensive pretty fast.”

After moving it out a storage unit in New Jersey and into a friend’s attic in Massachusetts, the couple, who currently live in a rural area about an hour outside of Aix-en-Provence, said they need to find a new home for the archive by Thanksgiving.

Their intention was never to have it in storage at all. Grifo has discussed archiving their objects with various institutions, but said the pieces don’t fit neatly into any existing collections.

“It’s a great study resource for, say, product design,” Grifo said. “But SVA in New York just doesn’t have the space” she said, referring to the School of Visual Arts in Flatiron. Having to move the archive a third time has lent the pair new urgency to finding it a proper home.

Both agree that KIOSK feels inextricably tied to New York, and especially to their original location at Spring and Broadway, a few blocks from where Grifo had lived since the mid-90s.

“Even then, SoHo was changing,” Grifo said.

“It was the center of the center of the consumer central of the United States,” she said. “Being positioned there, we wanted to help people change the way they were consuming: to slow down, to have something to reflect on, to purchase not just wildly, but with some context and intelligence, and hopefully purchase less as a result.”

In a twist out of one of Grifo’s own whimsical descriptions, she says Nike approached the couple about a KIOSK collaboration several years ago.

At a lunch meeting, the sneaker brand’s creative directors began to describe their fantastic new building, on the exact same footprint that had displaced the original KIOSK.

“It became clear after a while that they’d never visited us,” Grifo said. “They’d seen it online, or been told we were cool, or whatever.”

When the couple finally told them why KIOSK had closed, Grifo said their faces turned white.

“We never heard from them again,” Grifo laughed. “We actually thought it was a really interesting way to continue the project, in the same spot but now inside a Nike store. It would have been really fun.”

Clarification: This story has been edited to clarify Costello’s title.

19 fun and free things to do in New York City this November A Spike Lee exhibit opens at the Brooklyn Museum