A Brief History Of SummerStage In Central Park

June 4, 2019, 3:50 p.m.

The annual live music series kicks off this weekend.

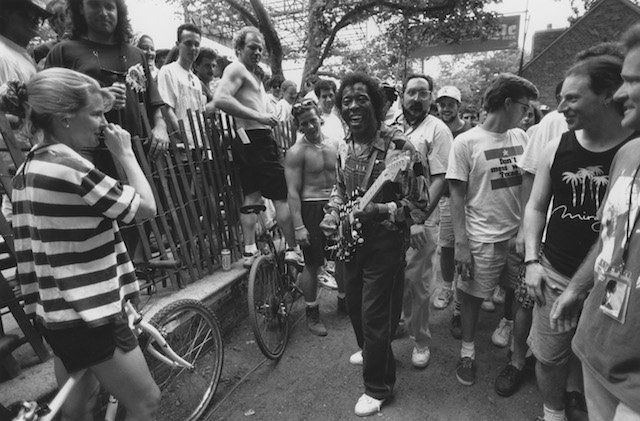

Buddy Guy leaping into the crowd for his SummerStage performance.

Over the past weekend, SummerStage in Central Park kicked off its inaugural season with a performance by Emily King and Durand Jones and the Indications. Audiences attending the annual outdoor performance showcase, located at Rumsey Playfield, can expect a completely different experience than in past years. "This time around we worked with an architect on the entire venue, and rethought how people move through the entire space," Heather Lubov, Executive Director of the City Parks Foundation, tells Gothamist. The stage recently got a $5.5 million overhaul that includes a new stage canopy, better sight lines throughout the space, VIP areas, and entrances and seating that are now fully accessible.

What hasn't changed is the range and variety of the series, which has been a mainstay in New York City since the mid-1980s. It's hard to imagine now, given the ubiquity of the summer music festival circuit, but back then the landscape for local outdoor music performance was hardly as established. With a few notable exceptions, one of them being BRIC's annual free live music showcase at the Prospect Park Bandshell, Celebrate Brooklyn!, which has been around since 1979.)

And while New York City has an illustrious history of performances in parks, ranging from free Saturday concerts in the Ramble back in 1859 to Barbra Streisand delivering a two-hour show at Sheep Meadow in 1967 (amidst shooting Funny Girl ) to Diana Ross performing in a storm, nothing like SummerStage's current iteration existed.

The audience at SummerStage in 1996, during a Tracy Chapman performance. (NYC Parks Photo Archive)

Joe Killian, the founder of Summerstage in Central Park, tells Gothamist that he first came up with the idea to do a concert series when he walked through the park one day, and passed by the spectacular Naumberg Bandshell in disrepair. There, he saw possibilities. "New York was a different city, and certainly Central Park was a different place," he says. "And I thought, 'Well, we could build a series there." [See our then & now photos showing how much Central Park has changed since the 1980s.]

The idea, he says, was to "let New Yorkers connect the dots between dance and spoken word and world music" with performances that reflected the breadth of the city's artistic communities, from avant-garde downtown scenes to uptown salsa. And to have it be free. Given that Central Park was amidst refurbishing the park—including historic gathering places, Sheep Meadow, which had recently been restored and had played host to the likes of James Taylor—Killian's idea for a series came at a serendipitous time.

Curtis Mayfield, clad in a SummerStage t-shirt, delivering one of his last-ever performances at the series. (Jack Vartoogian)

From there, things took off, and Killian booked the likes of Ladysmith Black Mambazo for their first performance in the United States playing solo, without Paul Simon, as well as the Bulgarian wedding band collective Ivo Papazov. Sun Ra Arkestra was one of the first performers that Killian brought on, and a few years later, the Arkestra returned for a memorable July 4th double bill with Sonic Youth. These kinds of collaborations, especially in a pre-Internet era, helped SummerStage stand out.

In the 1980s, it also wasn't common for musicians to play outdoors during the day—and what became something that first arose out of necessity became a linchpin for the series. "I would have preferred to do shows in the evening but the police at that time did not feel they could secure the area, the park, because it was very dangerous at the time," he says. "And everything would have to be on generators." But the afternoon shows, a diametrically opposed experience to a nighttime club show for musicians, made them "rise to the occasion," as he puts it. "Someone has to be competitive to say, 'Where can I take this audience? And Buddy Guy is one of those performers," Killian remembers. "He got offstage and went through the crowd." And for his SummerStage performance, the iconic Screamin' Jay Hawkins came out in a casket, rising from it—in the middle of a hot afternoon.

Inevitably, a lot has changed since SummerStage started. The brand new stage aside, Killian isn't involved anymore, and the series (which has since moved to Rumsey Playfield, in 1990) has expanded to include the likes of film screenings and dance performances, too.

The Bulgarian wedding band collective Ivo Papazov. (Jack Vartoogian)

Of course, it's also a transitional time for arts in the city. "We’ve seen the commercialization of the arts... most recently Hudson Yards with The Shed," Killian says. But along with that, something else has also emerged over the years: A greater emphasis on carving out avenues for people to take a moment to enjoy an afternoon of performance, whether that's at a free Central Park show or, as Killian notes, the spectacle of Times Square. "Times Square was a forbidden place or a dangerous place, maybe an attractive place in other ways, but when they redeveloped it, what did they build?" he says. "Essentially a set of seats, stairs, if you will, to watch the theater of Times Square. So I think what we’ve seen...[with] festivals out there is just a real growth of free assembly, I’d say. Some of it’s music, some of it’s theater, some of it’s dance. So I’m proud to have been maybe a spark for that."

See SummerStage's schedule here, where you'll find one of its early alums, the funk maestro George Clinton, who will be performing one of the final stops on his farewell tour at the park in June.