It's a historic townhouse, but 58 Joralemon is also a secret subway exit and shaft house owned by the MTA

Feb. 8, 2022, 5:01 a.m.

This Greek Revival Townhouse was built in 1847 as a private one-family residence, but now it could save your life if there's ever trouble in the subway tunnel below.

The building located at 58 Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights may look like a residential home at first glance, but the windows signal that something is a little off here. They're purposefully pitch black so you can't see inside, giving the quaint streetscape an ominous vibe to anyone paying close enough attention. Stop and listen and you may even hear some rumblings coming from the building—"probably just some regular ol' city noise," you'll think, brushing it off. But you'd be wrong.

This Greek Revival townhouse was built in 1847 as a private one-family residence on land owned by a judge named Teunis Joralemon, who had purchased a small section of the 40-acre Livingston estate (once owned by Philip Livingston, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a lawyer, and a slave trader).

Joralemon bought the land in 1804, decades after the Revolutionary War ended and when Willowtown—as this section of the neighborhood was, and is sometimes still, called—"was a thriving community with a lot of houses," New York Transit Museum curator Jodi Shapiro told Gothamist.

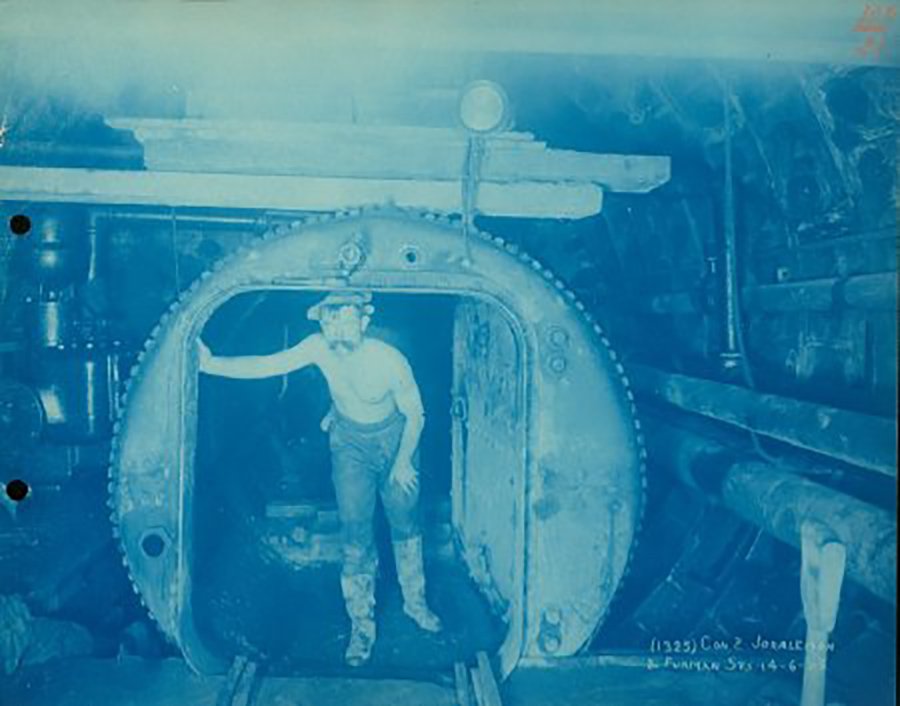

By the turn of the century, this area of Brooklyn was booming, and the subway system was being built, which would help connect its residents to Manhattan. As they plotted out where the tunnels were going to be between the two boroughs, 58 Joralemon was marked as a perfect spot. "It was situated right on top of where they wanted to build the first cross-river tunnel for the subway," Shapiro said.

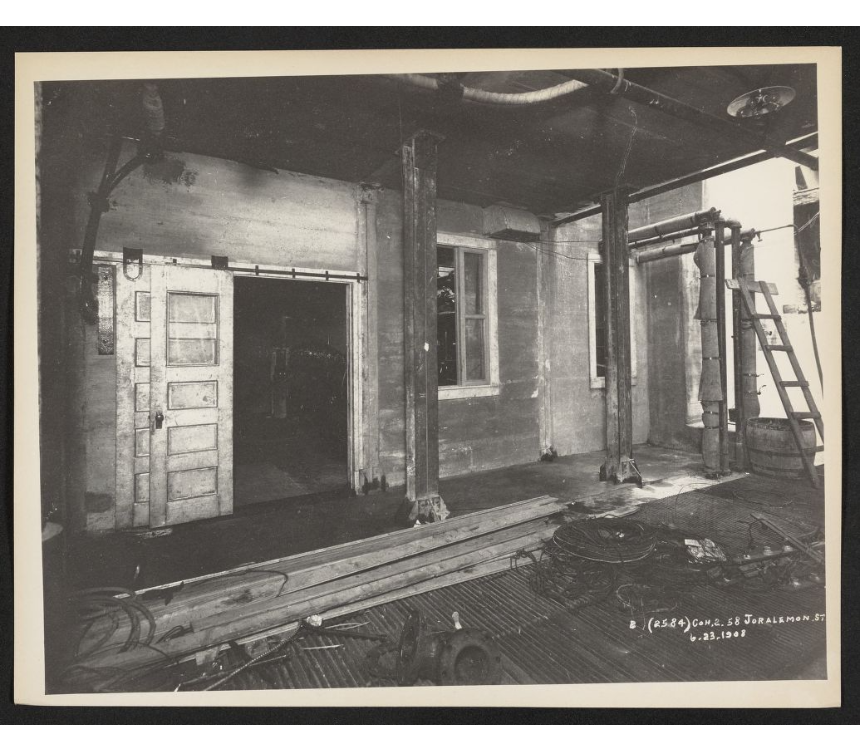

The Interborough Rapid Transit Company purchased the property in 1908, as construction was already underway in the area (including for Substation 21, just around the corner on Willow Place). Instead of knocking the townhouse down, however, the IRT dug underneath the building, which they then gutted and reconfigured to their needs as a ventilation shaft house.

Though they have updated the ventilation system in there a couple of times over the years, little else has changed—it's been an MTA property since the early 1900s, and also serves as an emergency exit where crew and passengers could escape if there were trouble in the tunnel. And if that trouble includes fire, the townhouse has a dual purpose—in addition to the exit, the ventilation system itself "can pull the smoke out of the tunnel" quickly, Shapiro said.

The below photo, provided by the Transit Museum, was taken from the stoop of 71 Joralemon Street and shows the construction of the Joralemon Street Tunnel on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line. Among the wheelbarrows of debris, you can see 58 Joralemon (it's the second townhouse from the left, where most of the workers are located).

While it used to be noisier, the shaft house has become quieter over the years. The MTA told Gothamist that they have indeed received noise complaints in the past when the team used to run fan tests at night. However, there's now a restriction that limits them to testing fans for maintenance during daytime hours. If there is an emergency, however, the fans could operate at night.

There's also some serenity offered to the direct neighbors, who are able to lease the backyard for a price. (We've asked the MTA for details on the current lease and will update if we receive more information; you can see photos of the backyard here, extending from 58 to 60 Joralemon, which is currently on the market.)

From the street, the structure itself blends in with the help of landmarking rules. Those black Lexan windows that alert passerby this isn't a typical home? They needed to be approved because the building is in a historic district. Because of this, any change to the exterior needs explicit approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and, in fact, the door on the building even has a historic lock set on it for this reason, in addition to the modern security locks.

But what exactly is inside of there? "There's all this speculation about what might be inside," Shapiro said. We were declined a tour, but she promised: "Honestly, it's really boring. If you were to walk in through the front door, right beyond is the catwalk to the staircase. It's just very industrial looking... a lot of structural ironwork in there." There aren't usually people in there, either, the MTA said the building is usually empty.

It's the exterior that has become the draw, making anyone who notices it question what secretive things are going on in there. And maybe it is a little magical, or at least unique.

"There are emergency exits all over our subway system," Shapiro said. "It's just that this one happens to be in a Greek Revival townhouse."